If social media had existed in 1487, this would have been the viral post that ended civilization.

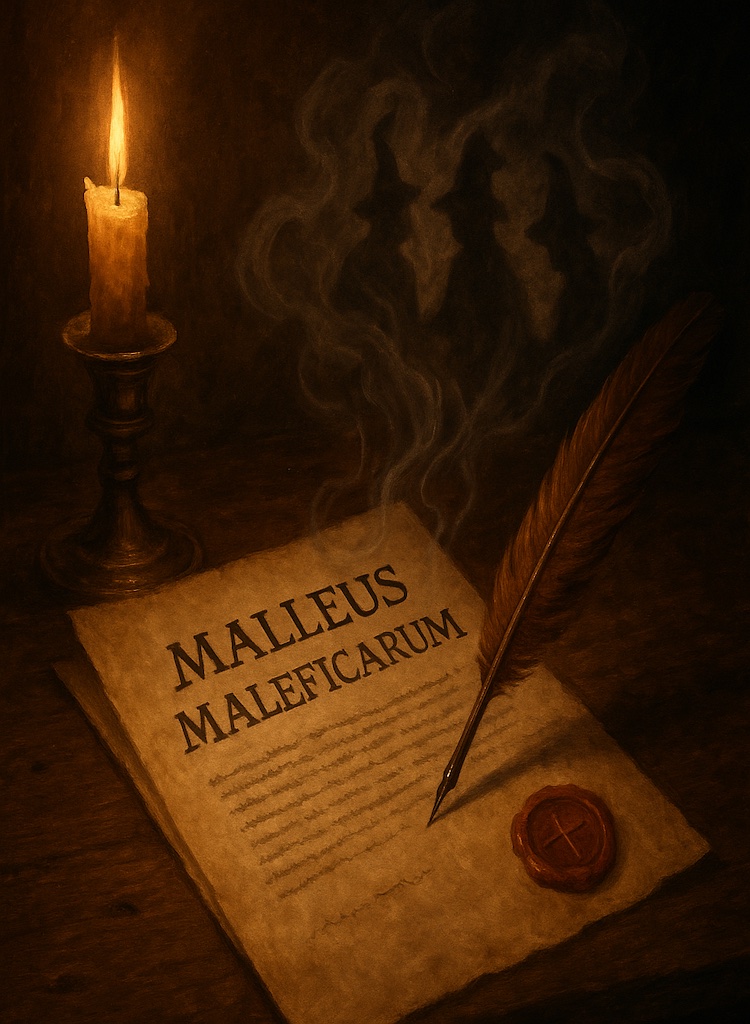

A Dominican inquisitor named Heinrich Kramer sat down with a quill, a grudge, and a mission: to prove that witches were not only real but everywhere — corrupting harvests, seducing priests, and making men “impotent in body and soul.” His book, Malleus Maleficarum — The Hammer of Witches — became the Renaissance equivalent of a global conspiracy thread.

Its first line strikes like lightning: “What else is a woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil.”

Charming, isn’t it? Kramer’s Latin prose reads like a fever dream of fear disguised as theology. He claimed witchcraft was a structured conspiracy, that women were the Devil’s preferred vessels, and that mercy toward them was treason against God. The book instructs inquisitors to extract confessions through “moderate torture,” to view denial as proof of guilt, and to see every female body as a potential crime scene.

It worked — spectacularly. Within a century, The Hammer helped justify tens of thousands of executions across Europe. It spread faster than any sermon, a viral algorithm of terror. Priests quoted it, judges cited it, and terrified villagers turned suspicion into scripture.

What’s wild is how modern it feels. Replace “witch” with “traitor,” “heretic,” or “enemy of the state,” and the rhythm is identical. Every age has its Hammer.

It’s the same playbook: accuse → divide → sanctify the fear → sell the cure.

Kramer’s theology reads like early PR for authoritarianism. His argument? The world must be saved from invisible forces, and only those in power can identify them. Sound familiar?

Today, we call it propaganda. In 1487, they called it holy work.

He even anticipates online discourse: “For if one were to deny the existence of witches, he would thereby deny the words of Holy Scripture.” Translation: disagree, and you’re already damned. It’s the 15th-century version of cancel culture by decree.

The real genius of Malleus Maleficarum isn’t its scholarship — it’s its simplicity. It turned complex social fears into a single, actionable narrative: blame someone weaker. That formula never went out of style. Few people realize that the Catholic Church itself later distanced from it, quietly shelving the “Hammer” once its fires burned too hot. But by then, the idea was free — carried by pulpits, fear, and the irresistible human need for someone to blame.

If you read it today, it’s not just history; it’s a mirror. A reminder that fear doesn’t age — it just updates its vocabulary.

“The Devil can act through the imagination of man,” Kramer wrote,

and perhaps he still does — through hashtags, headlines, and the quiet comfort of certainty.

Curious? The full text of Malleus Maleficarum can be read or downloaded from my website here.